A $150,000 contract let to consulting and services firm GHD in May this year suggests that the NSW government is still pursuing “major public transport initiatives” along Parramatta Road, despite media reports that it has scrapped detailed plans for a light rail line from Burwood to Sydney’s CBD.

Transport NSW has commissioned GHD to undertake a project titled “Transport Planning Analysis and Drafting Support – Parramatta Road Intermediate Transit”. GHD is expected to “Develop an overarching analysis and narrative that will bring together the major public transport initiatives currently being investigated for the Sydney to Parramatta corridor.”

The contract commenced in May and is expected to run until February 2019. No other detail is provided in the contract announcement but the specific use of the phrase “Parramatta Road Intermediate Transit” (PRIT) in the title is intriguing because it links the contract specifically to the road. The same phrase – followed by “Light Rail” in brackets – was also used in the title of some of the working documents on the light rail plans obtained by the Sydney Morning Herald.

It’s worth exploring the implications of the development of the light rail proposals and their scrapping by the government, as well as the significance of the subsequent decision to commission GHD to undertake further work on the intermediate transit project.

Light rail proposed…

The rationale for the light rail project echoes the findings of a procession of government reports over the past three decades: Parramatta Road suffers from heavy traffic and increasing levels of congestion which adversely affect land use, the environment and the built urban form along this corridor. The buses which run along it are slow and provide poor public transport service levels with little capacity for future growth.

Successive state governments have attempted to deal with these issues largely by bypassing them – and the road – through the staged construction and subsequent widening of the M4 motorway. This approach may have increased road capacity in the corridor between Parramatta and the city but only a few incremental changes have been made to the Parramatta Road itself.

The latest motorway project, WestConnex, presents a real opportunity to change the road’s fortunes. Whatever the flaws of WestConnex (and they are considerable), this immensely expensive tollway should result in some reduction in traffic volumes on Parramatta Road, a goal which is reinforced by a condition of the project approval that two lanes along the road are to be reserved for public transport unless a better alternative is developed.

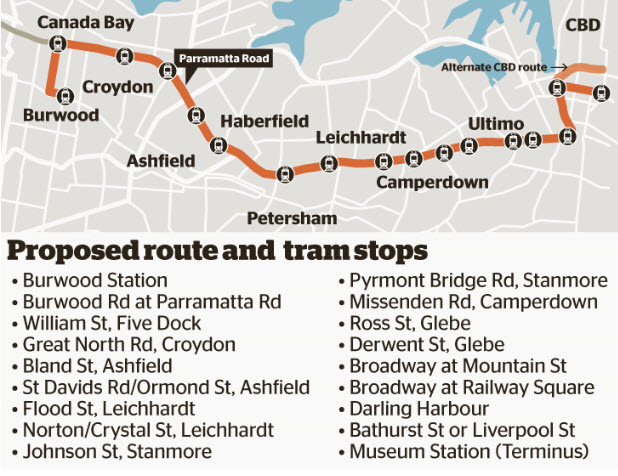

The provision of a light rail line, a concept which has been discussed for decades, was the government’s initial response. Under the PRIT proposal this would have taken the form of a 13km line with 18 stops starting next to Burwood Station. From there it would have run northwards along Burwood Road, turning east into Parramatta Road before heading into the city via a potential interchange with the existing Inner West light rail line at Taverners Hill.

At the CBD end it would have turned off at Railway Square into Quay Street, passing next to Darling Harbour and crossing the Inner West LR again before turning east into Liverpool Street. It would then cross the CBD light rail line currently under construction in George Street to terminate next to Museum Station. An alternative route would have taken the line along Bathurst Street.

Detail of the PRIT proposed route, showing potential interchanges with the existing Inner West Light Rail line

On paper, the project would have responded to many of the issues identified in the project rationale and in particular the need to increase the reliability, capacity and speed of public transport services. It would have reduced travel times from 39 to 22 minutes and also provided an opportunity to restructure bus routes throughout the inner west so that they would act as feeders to the PRIT project rather than continuing to run to the CBD.

The line would have serviced a number of major destinations along Parramatta Road and Broadway, including the University of Sydney and the University of Technology as well as RPA Hospital. At the city end the line would have also acted as a fast cross-city link between Darling Harbour and the eastern edge of the CBD.

… and then scrapped

It is tempting to blame the PRIT about-face on an increasing degree of ambivalence about light rail within government. On the one hand, the Inner West and Queensland’s Gold Coast lines have been extremely successful and the NSW government is pressing ahead with its light rail plans for Parramatta and Newcastle. On the other, the CSELR project currently under construction has faced strong opposition due to its environmental impacts and disruption to local businesses. In addition, the cost has blown out by $500 million to over $2.1 billion.

Ironically however, the most likely contributor to PRIT’s termination (at least as a light rail project) is planning for the other major public transport project announced by the government for the Parramatta Road corridor – Sydney Metro West. Publicly-available information about Sydney’s second planned metro is even more sketchy than the leaked plans for PRIT; all we know is that it will run from Parramatta via Sydney Olympic Park (SOP) and the Bays Precinct to an interchange with the one of the CBD stations on the metro line currently under construction.

The proposed route between SOP and the Bays Precinct is still a complete mystery. There are several options (some of which I canvassed in a series of articles last year) including the potential for part of this central section to run close to Parramatta Road. If this route is selected and the PRIT had gone ahead there would have been great opportunities for integration – but also the potential for wasteful duplication.

Even if the metro ends up running further north and does not intersect with Parramatta Road, PRIT would have added a fourth major east-west link, after the existing rail line, the planned metro and WestConnex. It would have also involved spending an additional estimated $2.6 billion on top of the metro’s estimated cost of $12.5 billion, billions more for WestConnex and upgrades to the rail line.

After allocating all the proceeds of the electricity assets leases, $2.6 billion may be money the government simply does not have. And even if it did, the expenditure of this amount to provide a fourth link in a corridor only 20km long and around 3km wide would clearly have been difficult to sell politically as a high priority to the rest of NSW.

Finally, while PRIT’s run along Parramatta Road would have been fairly straight-forward, the planned entry into the CBD appears very awkward. The logical route would be straight up George Street but this has been taken for the CSELR. While in theory PRIT and CSELR could share tracks all the way to Circular Quay the combined patronage levels would simply be impossible to service with light rail, especially given the capacity issues of the latter.

Instead the plans called for PRIT to turn off George Street only 200 metres short of where CSELR joins on and then to enter the CBD via an indirect dog-leg, terminating well south of the central part of the CBD. This would have forced many commuters to change to another mode – including an overcrowded CSELR – for the last section of their journey.

If light rail is dead, is “intermediate transit” still alive?

While the government appears to have killed off light rail, the GHD contract strongly suggests that the PRIT project is likely to continue in some form. And although there is a good argument for light rail along Parramatta Road there is also a strong case for looking at “intermediate transit” alternatives which could deliver similar outcomes at lower cost.

The claim about reduced travel time for PRIT is a case in point. It is unclear what proportion of the estimated 17-minute reduction would be due to the superiority of light rail technology over buses or, simply, to the reduction in the number of stops along the route (incidentally it is also unclear what contribution the forecast reduction in traffic volumes along Parramatta Road after WestConnex opened would have made to these estimates).

The following is largely speculative, but the most obvious intermediate transit alternative to light rail is some form of bus rapid transit (BRT). There are already peak-hour bus lanes along much of the route which could be converted into a 24-hour limited-stop bus corridor following the same route proposed for the light rail.

This would be similar in concept to the Northern Beaches BRT currently under construction; even if the somewhat exorbitant $600 million price tag of this project is used as a guide, the cost of a similar exercise along Parramatta Road is likely to be a lot lower (and politically more acceptable) than the $2.6 billion required for light rail. If the government were to aim a little higher it could also look at using electric buses or even guided electric vehicles, as recently proposed by a number of councils along the route.

These alternatives would however provide lower capacity than a light rail corridor and a larger number of vehicles (buses) would be required. This exacerbates a problem they all share with the light rail proposal – how to enter a crowded CBD, especially given that the CSELR will monopolise the George Street corridor from 2019 onwards.

Depending on the final route selected, the planned metro could provide an interesting alternative approach. As noted earlier, the metro could have been integrated with the proposed light rail line – and the same applies to a bus corridor.

One of the options I suggested for the metro route in the article series I mentioned earlier would involve three stations on Parramatta Road; one between Burwood and Five Dock, a second at Taverners Hill and a third at the western end of the University of Sydney. A Parramatta Road bus corridor could be designed to use stops like these as interchanges which would provide opportunities for passengers to change to the metro for significantly faster trips into the CBD and to Parramatta. This approach would reduce the number of buses entering the city and would also support a restructured bus network with more north-south routes.

I have no idea if this sort of approach is under consideration but it would fit with the GHD brief, for an “overarching analysis and narrative” bringing together all the major public transport initiatives under investigation in this corridor. Light rail as a form of intermediate transit along Parramatta Road would make a lot of sense in the absence of a metro, but the construction of the latter provides an opportunity to design an efficient bus-based system – assuming the right alignment is chosen for the metro.

In this regard the NSW government needs to be a lot more transparent about its plans and to think much more strategically. It would be very disappointing if it planned to walk away from PRIT entirely and to use the GHD contract as a form of window dressing to hide its retreat. Whether “intermediate transit” in Parramatta Road takes the form of light rail or a bus rapid transit system is much less important than that it is actually provided and fully integrated with the proposed Sydney West Metro.