Australian cities have come relatively late to the light rail revival which spread across the globe in the latter decades of the 20th century, but lately they seem to be making up for lost ground. There are now three substantially new or renovated lines in operation – and that’s not counting Melbourne substantial tram network – with two more on the way and several others on the drawing board.

Before I take a closer look at these, it’s useful to go over a little history. While Melbourne maintained its role as a major tram city (with one of the largest systems in the world), by the 1960s trams were removed in all other cities except for the light rail line in Adelaide.

It was not until the late 1990s that the first sign of the modern light rail revolution appeared in Australia, with the conversion of a relatively short section of a freight line in Sydney in 1997. Even then things happened slowly – while there were some extensions in Adelaide and Sydney in the 2000s, it was only after 2010 that the revival really took off.

Further extensions to these lines were completed and most significantly of all, in 2014 a completely new line not based on an existing rail corridor was opened on the Gold Coast. In addition two more new lines are planned which have strong government commitments to complete them by 2019 – a second line in Sydney and a line in Canberra.

In summary, by 2020 Australia could have five modern light rail lines in four cities. Conveniently of similar length and with broadly similar technologies, these provide a basis for comparison which provides some insights into why this revival has occurred and the direction of public transport planning in Australia.

I’m going to try to tease some of these issues out in this series of posts, though before I do so I should attempt to define exactly what “light rail” is. This will always be an inexact process because there is a considerable degree of overlap with other modes of fixed wheel transport – trams on the one hand and conventional rail on the other. However a good working definition is provided by the American Public Transportation Association:

“…a mode of transit service (also called streetcar, tramway, or trolley) operating passenger rail cars singly (or in short, usually two-car or three-car, trains) on fixed rails in right-of-way that is often separated from other traffic for part or much of the way”.

I agree with this except that I would put stronger emphasis on the level of separation from other traffic, which provides the key distinction from traditional tramways. All the lines I’m going to talk about – the ones already operating in Adelaide, Sydney and the Gold Coast, along with the line proposed for Canberra and the second line planned for Sydney – are consistent with this definition. Parts of the Melbourne system are too, but that is still predominantly a street-based tramway. It is also not easy to incorporate Melbourne into any comparison as it is, literally, 20 times the size of any of the light rail lines in the other cities.

In the table below I’ve attempted to make a detailed comparison between the three light rail lines currently operating and the two which have solid government commitments. Apart from Melbourne, other systems not included are the proposals for Hobart and Perth which are either uncommitted or deferred, the plan for Newcastle in NSW, for which there is relatively little information and those for Western Sydney which are yet to be finalised. This table is available in a more readable PDF format here and will be the basis for this series of posts.

I’ll talk about some of the key similarities and differences between these systems and what we can learn from their development, starting in this post with a brief overview.

Status: as stated, lines in Adelaide (Glenelg Tram), Sydney (Dulwich Hill Line) and the Gold Coast (G:Link) are in operation. Contracts have been let for the CBD and Eastern Suburbs Light Rail (CESLR) with construction due to start later this year. The future of the Capital Metro project in Canberra is less secure; while two consortia have been shortlisted no contracts have been let and the ACT Assembly opposition has vowed to scrap the project if it wins office in next year’s election.

History and description: By far the oldest light rail line is the one in Adelaide, which opened in 1929 after a conversion from a heavy rail suburban line. It operated continuously using the original tram cars until 2007, when the first CBD extension was opened and the rolling stock replaced. The second CBD extension was completed in 2010.

The line now runs from a beachside terminus in Glenelg to the south western edge of the Adelaide CBD which it transects along the main north-south corridor before turning left running past the railway station to the entertainment centre which also has extensive parking. The line therefore provides radial commuter services from one end and a park-and-ride service from the other.

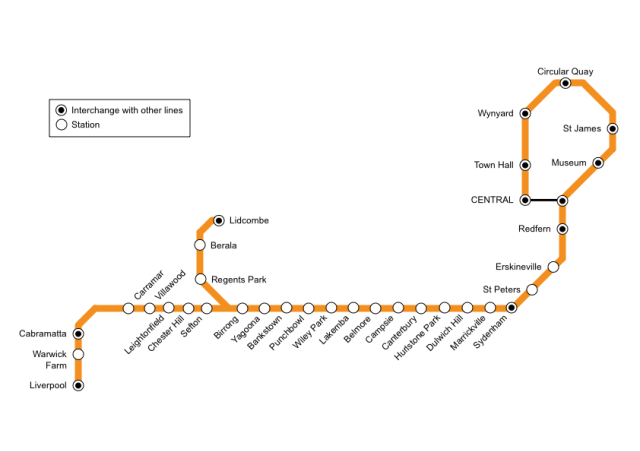

The second line to open was the Dulwich Hill Line in Sydney, in 1997. This line which is also based on the conversion of an existing railway (in this case, a freight line) from Central Station, was extended to Lilyfield in 2000. This section provides connectivity to major entertainment facilities in Haymarket and Darling Harbour as well as radial commuter services, though only as far as the southern end of the CBD.

The most recent extension, opened in 2014, extends the service as far as the end of the old freight line in Dulwich Hill where there is a second interchange with the rail network. This section provides both CBD commuter services and circumferential services between various bus and rail corridors in inner western suburbs.

As noted earlier the most significant development in recent years has been the opening in 2014 of the Gold Coast light rail line. Unlike the other systems this was not based on any existing rail corridor but was developed from scratch to provide a central transport corridor through the city, linking key centres and providing commuter services.

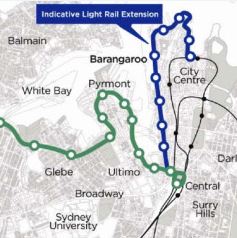

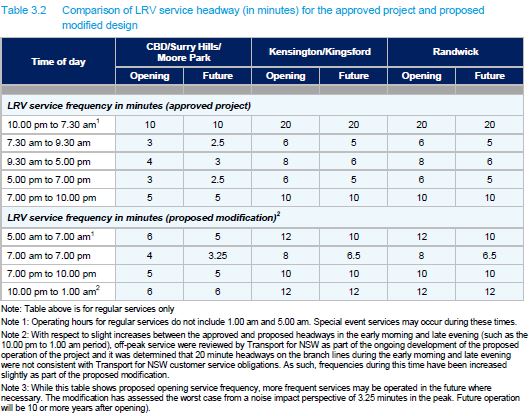

While the about-to-be-constructed CESLR in Sydney will be of similar length to the other lines it will be of an entirely different scale in terms of capacity and patronage. These issues will be discussed in future posts (and I have also discussed the CESLR itself in an earlier series of articles starting here), but the line due for completion in 2019 will replace a large number of commuter bus services in the city’s eastern suburbs as well as providing a circulation service in the CBD’s main north-south corridor, which will be pedestrianised.

Finally, the Capital Metro in Canberra will if constructed provide commuter services from the city’s north to the city centre – and if an extension to Russell is approved, through part of the CBD. This line is also due to be completed in 2019, but as mentioned earlier the prospects for this line’s completion are mixed with the ACT opposition committed to abandon the project in favour of improved bus services.

In my next post I will look at some of the technical and operational aspects of these three existing and two planned services and in future articles discuss some of the implications of this rapid expansion of light rail in Australia.